Prospects for regional integration in West Africa*

Manfred Hedrich and Klaus von der Ropp

ABSTRACT: Africa has seen a number of plans to integrate and merge the economies of various groups of states. Most plans simply remained on paper or made no progress after the first few steps, while the supposed model case in East Africa has been formally dissolved. However, in West Africa, particularly in the French-speaking area, several institutions which have coped successfully with the initial phases of an economic community and which seem to have a clear future have been created. Economist Manfred Hedrich, and Dr Klaus Frhr. von der Ropp of the ”Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik”, Bonn, both of whom have had many years of experience in Africa, proceed on the basis of the fundamental problems posed by the integration of developing countries and examine the prerequisites for actual possibilities and the conditions which must be recognized by countries interested in such integration. In view of such criteria, the ”Communauté Economique de l'Afrique de l'Ouest” (Economic Community of West Africa) which includes Senegal, Mauritania, Mali, Niger, Upper Volta and the Ivory Coast would seem to be a special case. It has completed its development phase, and it is possible to evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of the mechanisms which have been created and to form an impression of the tasks lying ahead in the course of the next phase. By comparison, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS, or CEDEAO in French) that includes all 16 countries in West Africa, seems to have poorer prospects for success. Its members are too disparate, Nigeria's domination is too great and the governments are to some extent too different. This makes it difficult to foresee economic co-ordination and liberalisation. Moreover, it is not clear how the CEAO and ECOWAS can be united unless the Six decide to abandon the progress they have already made.

- * This article also appears in Aussenpolitik (German Foreign Affairs Review), vol. 29, Quarterly Edition, no. 1, p.87—101

Introduction

The announcement by Kenya's Attorney General, Charles Njonjo, on 29 June 1977 to the effect that the East African Community (EAC) would cease to exist the next day did not come as a surprise to the rest of the world (Baumhöger, G. 1976). This was the beginning of the final liquidation of an attempt at integration that can be traced to between 1917 and 1927 and which for good reasons had come to be regarded as the model for co-operation among developing countries, not only in Africa, but also in the rest of the Third World. In fact, the establishment of the East African Common Services Organization, and the East African Income Tax Department aswell as the introduction of a common currency, the East African shilling, made it possible to achieve a considerably higher degree of integration in certain important areas than has been the case within the European Community until the present.

Africa's Quest for Unity

On the basis of events in post-colonial Africa, the proposals made in the second half of 1977 by various political figures in East Africa, for the creation of a Greater East African Community, including Zambia and Mozambique as well as other states, should not be taken all that seriously. This would also seem to apply to plans, to establish an African Economic Community to include all African countries, repeated at the 11th Special Session of the OAU Council of Ministers (Kinshasa, December, 1976) and then forwarded to the OAU General Secretariat and the Economic Commission for Africa (ECA) for further study. In general, the motive behind all similar and comparable initiatives by African politicians is more apt to be political rather than economic considerations, explaining the failure of many attempts at integration and the fact that it is often possible to predict this in advance. (Von der Ropp, K. Freiherr, 1971.) Nevertheless, certain factors, such as common efforts to introduce a "New International Economic Order”, the stance African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) countries are expected to take in the renewal negotiations of the Lomé Convention (that expires on 1 March 1980) and the EC's attempts to expand to the south will provide Africa with incentives to make renewed attempts to find its own way to stable unity. As a result, the fact that the EC is promoting promising plans for integration among the ACP countries and in Africa in particular, in many different ways, can only be considered positive. This is reflected in Article 47 of the Lomé Convention that states that the EC will provide effective help to achieve the goals set by the ACP countries with respect to regional and interregional co-operation. Some aims of this assistance are accelerated co-operation among ACP countries, import substitution by domestic products and the creation of sufficiently large markets. Approximately 10 per cent of the funds provided in Article 42 of the Convention for economic and social development of ACP countries has been allocated to finance regional projects. These funds amount to approximately 400 million European accounting units.

West Africa as Focal Point

Projects promoting integration in West Africa are prime candidates for such assistance, particularly after the dissolution of the EAC, and they are to be given preference over others. In recent years, West Africa has become the focal point of efforts to achieve integration in Africa. The two economic communities, the Communauté Economique de l'Afrique de l'Ouest (CEAO) and, to a lesser extent, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), merit special mention. The CEAO established in 1973 consists of six member states, Senegal, Mauritania, Mali, Niger, Upper Volta and Ivory Coast, (”les ‘Six’ de l'Afrique”) (Le Moniteur Africain, 1973.) The ECOWAS, or CEDEAO, founded in 1975 includes all 16 countries of West Africa. The six countries mentioned above are therefore members of both communities. In this context, it has been said that the CEAO countries are attempting to establish a position within the ECOWAS, comparable to that of the Benelux community within the EC, (Houphouet-Boigny, Felix, 1977), or in other words, that they are trying to establish the CEAO as the core of the ECOWAS. To borrow a phrase used in discussions concerning European unity, one might speak of an ”Afrique à plusieures vitesses”, an "Afrique à géométrie variable". However, it is imperative here that theconstitutions of both communities be compatible (this is dealt with in more detail below). One might simply mention that there is much evidence to the effect that this is not the case. In other

words, the present legal situation does not allow the two communities to exist at the same time. It would be as well to preface this discussion with a few basic considerations concerning the integration of developing countries as this is the only way to develop criteria for judgement which can be applied to attempts being made in West Africa.

Problem of Integrating Developing Countries

The problem of integrating small countries (small in the sense of market size, population and internationally saleable raw materials and or services) must be seen in the context of development possibilities and indeed, in the context of the longterm survival of these countries.

Previous attempts at integration have shown that the prospects of success are not favourable in the case of countries with similar economic structures at a low level of development. Long-term advantages for all participants can only be guaranteed if the sectors to be integrated are complementary and if at least one of the participants is at a higher level of development, enabling it to make the necessary compensation payments from "substance" which already exists. Apart from political (foreign policy) considerations with respect to the threat of domination by a stronger partner, previous efforts usually failed because the problem of compensation could not be resolved. In previous efforts there have always been countries in more favourable situations, but they have regularly been incapable of compensating the less favourably placed countries for indirect long-term losses resulting from the polarizing effects of integration. Economic integration as the core and basis of complete integration of developing countries should be considered more a process than a final result. This process is one in which equal partner countries from the same region with similarly oriented economic interests first co-ordinate certain areas (sectors, sub-sectors, policies) of their national economies and only then gradually adapt their respective economic structures to establish a single entity in the sense that changes in the structure of the respective integrated areas are only made in accordance with uniform criteria decided by a single decision-making body.

Basic Prerequisites for Successful Integration

Experience has shown that efforts to achieve integration will be unsuccessful unless the following basic conditions exist:

- The necessity of integration (resulting from external pressure from political constellations outside the area and from the investment policies of international concerns; or compelling internal factors, such as restricted markets).

- The conviction on the part of all concerned that integration will lead to a better political and/or economic future.

The first condition is generally relatively easy to recognize, but the second is far more difficult to ascertain due to problems associated with anticipation in a non-integrated situation, and the uncertainty with respect to evaluation of direct and, in particular, indirect effects of integration. Integration will be short-lived unless all parties concerned concur on the following five categories which have to be clearly formulated:

- A common goal or complex of goals to be achieved through integration (the number of goals in such a complex must be limited and the goals must be interrelated);

- the effects upon participant countries and any non-participant countries with which participant countries have existing ties (trading partners, transit countries, etc.);

- the schedule for implementing the successive steps in the process of integration and the criteria for evaluating the success of each phase;

- the institutions affected by integration, their executive, control and information functions; and financing (quotas and financial plan).

Relation between Partial Integration and Complete Integration

The obligations with respect to individual goals of partial integration and the effects of intensi-

fied interaction resulting from integration of the subsystem are of decisive importance for the process of complete integration. This means that attempts at partial integration do not automatically set in motion a process in the direction of complete integration. The notion of obligation means that all participants must be prepared not only to allow the effects of partial integration to run their natural course within the integrated subsystem, but they must also allow these effects to influence other subsystems or at least not stand in the way of such developments. Strongly interrelated subsectors that make co-ordination or integration of advanced and retarded subsectors compulsory for technological reasons, or desirable for economic reasons, can more easily be completely integrated than others, but at the same time these are the areas which contain the greatest potential for conflict.

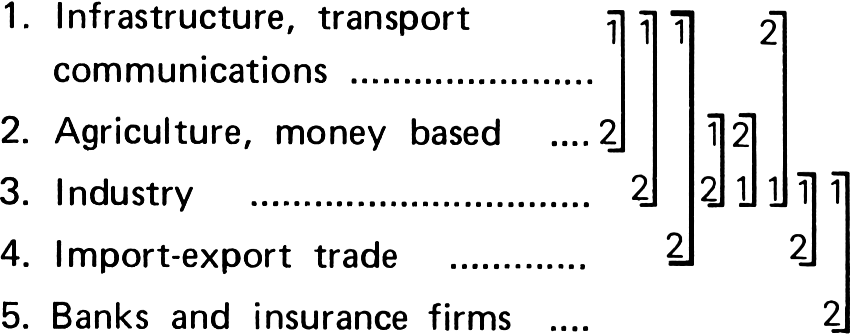

It is possible to isolate the following five main sectors which are amenable to integration, but the sector in which partial integration first takes place is of absolutely no importance in the process towards complete integration:

(The brackets indicate the interrelated effects which are assumed to be the most important in making the transition from successful partial integration in 1 to 2.)

The optimum size of the area to be integrated and the degree of difference (or similarity) with respect to levels of development in countries interested in participating in such a process of integration, are still unresolved problems.

The optimum size of the area is evidently dependent upon the optimum size of the most important sector to be partially integrated, i e, the sector manifesting the greatest number of resultant interrelations, as determined by commercial criteria (plant size). According to the above illustration, this would be industry. The overall optimum for an area to be integrated does not therefor consist of the sum of the optimum values for partial integration because the optimum sizes for infrastructure, agriculture, etc, are not the same as those for industry. If the process of integration gives rise to the necessity of limiting the area regionally, then the size of the area should be determined in accordance with the criteria for the optimum size of the core or key sector of integration.

The question as to the degree of difference with respect to levels of development also entails the problem of industrial or economic centres as opposed to backward areas in a given region.

In the initial phase of integration, existing differences resulting from the attractiveness of the location of industrial centres would probably even tend to increase. The effect of this is that it is only possible to introduce a stabilizing element into the process of integration by means of massive compensation to the "backward" countries which do not benefit equally from the process of integration. A redistribution of the uneven net gains from integration would initially have to take place at the expense of the industrialized centres. An equilibrium with respect to the distribution of revenue can only be achieved gradually after the “backward” areas have developed structures in respect of infrastructure, agriculture and industry that allow them to benefit from the process of integration.

Conclusions

The above considerations give rise to the following conclusions with respect to the prospects for lasting success in attempts at integration among small countries

- All direct and indirect costs and revenues resulting from integration must be determined, and all parties must agree that any "deficits" will definitively be covered by specific compensation funds.

- Compensation must not only consist of direct financial transfers to compensate for decreases in fiscal revenues from industrial production, but also of community structural funds to finance investments in the disadvantaged countries. Beyond that, these countries must be enabled to participate in the capital structures of industries established in the more prosperous countries.

- In addition to the compensation mechanisms designed to correct defects in the process of integration, common development plans and industrialization policies must also be implemented.

Accordingly, the emphasis of co-operation during the first phase of integration must be on obtaining adequate financial means to establish the compensation and structural investment funds. Most attempts at integration by developing countries failed because of inadequate financing for these funds despite the existence of a compensation mechanism which was well thought out theoretically and despite a political desire to achieve unity.

Attempts at Integration in West Africa

The many attempts at integration in West Africa have resulted from:

- The existing particularly acute political and economic disparities; and

- the French language as a common basis for all efforts (with the ECOWAS (Scherk, N 1968 & von der Ropp, K 1974) as an exception.

Without making any attempt to treat them in more detail here, the following institutions, some of which have been definitely successful, can be mentioned: the Union Monétaire Ouest-Africaine with the Banque Centrale des Etats de l'Afrique de l'Ouest, the Organisation de Mise en Valeur du Fleuve Sénégal, the Autorité Intégree de Liptako-Gourma and the Communauté Economique du Bétail et de la Viande des Etats de l'Entente. Furthermore, there are the CEAO and the ECOWAS.

In addition to these institutions of West African countries, organizations promoting integration have also developed in the private sector and in other non-governmental areas in recent years. The most important since 1972 is the Fédération des Chambres de Commerce de l'Afrique Occidentale that has assumed responsibility for promoting closer co-operation among the chambers of commerce and economic organizations in the region. This organization concentrates its efforts on the exchange of information on market developments among its members and on advising governments on matters concerning the expansion of trade within the region.

An overall balance and prospects for the future for two particularly important and at the same time exemplary institutions will be attempted below. Factors indicating the importance and exemplary nature of these two institutions will be measured against the conclusions derived from the above discussion of basic considerations.

Despite their differences with respect to goals and the number of member countries, the CEAO and the ECOWAS share at least four common features which meet the main requirements for lasting co-operation among or (partial) integration of developing countries and (making it possible to avoid several mistakes made by the East African Community): they have adequately functional institutions; they limit their activity to economic considerations; they act in accordance with more or less clearly recognizable planning phases; and they are characterized by the flexibility with which they handle administrative matters.

The "Communauté Economique de l'Afrique de l'Ouest"

The Communauté Economique de l’Afrique de l'Ouest (CEAO) is no doubt already the most important of the two organizations, if for no other reason than because it can point to initial success after only four years of legal existence and three years of actual operation and — although provided only with modest means - because it has successfully applied the compensation mechanism (Fonds Communautaire de Développement), which is all-important for the initial phase of integration (Langhammer, R J , 1973; von der Ropp, K, 1973 & Mytelka, Lynn, K, 1974). The CEAO is steadily gaining respect on the international level and is being consulted more and more on the pan-African level for advice on the establishment of co-operation arrangements.* The organization is becoming increa-

- *Two recent examples are the inclusion of the CEAO in the planned co-ordinated operations of the regional development-financing institutes, the Banque Ouest-Africaine de Développement, and the Banque Africaine de Développement, and the joint resolution by the Club of Rome and the Club of Dakar to pursue for the first time the concrete application of the Mesarovic-Pestel model to one region, and to choose the CEAO for this on the recommendation of President L Senghor of Senegal.

It is a good idea to develop this theme in a world where a general tendency toward regional alliances exists. The necessity of close co-operation between the smaller countries of the region to overcome their limited economic basis, which also poses a political threat to their existence, is no longer doubted by anyone.

Although it is premature to attempt a complete evaluation of the Community's performance after only three years of actual operation, it would nevertheless seem possible to identify the strengths and weaknesses of the CEAO’s mechanisms and make a statement on its probable future development. A sober comparison of the per capita income for 1970 and 1974 shows that the efforts to reduce the difference between rich and poor countries belonging to the Community are considered to produce results in the very near future; and in fact, the institutions are under considerable pressure to show positive results. This comparison reveals an unfavourable tendency which has probably not changed from 1975 to 1977 despite the general economic improvement in the Sahel countries since the catastrophic drought: assuming that the difference between the richest and poorest member states was 500 percent in 1970, the gap for 1974 had already increased to 575 percent. If the two poorest countries (Upper Volta and Niger) are compared with the two most highly developed countries (Ivory Coast and Senegal), the respective values would be 407 percent and 465 percent. The rate at which this divergent tendency is proceeding is the same in both cases. (Le Soleil, 1973).

First results of the initial phase

The initial phase of integration has resulted in the development of institutional structures that, with the exception of the authority for transportation and communications and an information and documentation centre, not specifically provided for in the agreement itself, already exist to the extent planned. The solidarity fund and an agreement covering non-aggression and defence-related assistance are new additions which followed the most recent summit conference of the CEAO Heads of State in Abidjan in June 1977 (Jeune Afrique, 1977). The CEAO Secretariat is staffed by about 30 senior civil servants,and functions with practically no assistance from foreign experts.

Although communication between the Community and the individual states often leaves much to be desired, especially in the area of statistics concerning trade within the Community, this can definitely, with few exceptions, be traced to the national authorities responsible for customs statistics which have as yet not developed the required capacity. Such statistics are of considerable importance as a basis for evaluating losses in customs. Following the establishment of the CEAO, compiling trade statistics became even more difficult as a result of new forms, a greater number of time-consuming informational seminars, and the fact that co-ordination with the various national authorities has not yet become routine*. A result of this for example, was that figures on the actual decreases in customs revenues of the individual countries for 1976 were not available in September of 1977, although they provide the basis for determining contributions to the Community's development fund (Fonds Communautaire de Développement FCD). Consequently, the FCD was provisionally allocated about 1300 million CFA francs for 1977, an amount which was 44 per cent lower than that for the preceding year.

Financial compensation

The CEAO’s central instruments for financial compensation, the Taxe de Coopération Régionale (TCR) and the FCD, both of which have only been in effect since January 1, 1976, have already been mentioned. (Von der Ropp, K, p 472—473). Because they have been in existence for a short time only, conclusions with respect to their activity are subject to revision. The TCR is derived from a contribution from CEAO countries that voluntarily give up part of their tax revenues from trade with partner countries. This tax is applied in the importing country in lieu of all

- *As a result, the General Secretariat's proposal that an official CEAO correspondent be appointed in every member state would seem justified. He would be responsible for co-ordinating all CEAO activities at the national level.

other customs duties and import taxes. The right to apply this tax is granted for a specific period of time upon application, and it only applies to specific industrial products manufactured within the Community if their value has been increased by at least 40 percent. The advantage of this tax for firms lies in the simplification of customs procedures, and in the possibility of having the price of the product lowered. It also seems that a solution has now been found for handling trade in raw materials that has constituted a problem in the past.

However, this solution is not being applied in all member countries. In accordance with this scheme, 60 percent of the raw materials for original products must originate from the Community.

The TCR is based upon an unwritten rule which has, however, subsequently become generally accepted. In accordance with this rule, the three land-locked CEAO countries, i.e. the countries with the weakest industrial bases, are treated preferentially when determining TCR rates if competitive products are produced in the other countries. This principle is also applied in determining percentages of raw materials. The "head start" of the three land-locked countries amounts on an average to between 10 and 20 percent. As long as these countries continue to play such a subordinate role in the process of industrialization, this “soft” arrangement will not present any problems and will therefore still be tolerated by the strong countries for some time. Statistics from 1976 on the number of TCR agreements, which the Secretariat published in its annual report, show the extent to which Ivory Coast and Senegal have been favoured by their location: According to the estimates of the Secretariat, this includes all industrial goods which could conceivably be covered by the TCR scheme at the present time. With respect to the actual practise of applying the TCR since it came into existence one-and-a-half years ago at least two weaknesses have become obvious. These will have to be eliminated in the near future in order to avoid inhibiting the continued development of this mechanism. The weaknesses result from the fact that a given agreement is only in effect for a period of one year and that the complicated computations to determine the percentages of raw materials and the tax rates for each product can only be "afforded" by larger industrial operations. At present, this system results in a large number of rejected applications that considerably discourages applicants. Another problem is found in the so-called "exclusivity clause” concerning the export monopoly that can be granted to a firm in one of the member states under certain conditions. Under this arrangement, other manufacturers of the same product cannot benefit from the TCR. A study of the criteria for granting such monopoly rights is presently being made.

Article 14 of the CEAO agreement ties the TCR to the FCD. This relationship becomes clear for the individual partner countries if the revenue losses (I), the FCD compensation payments (II) and the contributions made to the FCD by the member states in accordance with Article 34 (III) are compared. (See Table 2.)

The figures show that three countries in particular, namely, the Ivory Coast, Upper Volta and Mauritania, are markedly oriented toward the Community with respect to their import trade. The fact

Table 1

TCR Agreements for 1976

| Country | Number of plants | Number of products | Percentage of total production |

| Ivory Coast | 81 | 269 | 47,4 |

| Senegal | 52 | 217 | 38,3 |

| Upper Volta | 6 | 17 | 43 |

| Mali | 10 | 43 | 7,6 |

| Niger | 5 | 21 | 3,7 |

| Mauritania | - | - | - |

| 154 | 5671 | 100,0 |

- In fact there were only 501 products approved. The higher figure is a result of particular products being counted in respect of several countries.

Table 2

Estimated Amounts for 1977 in CFA Francs ('000000)

| I Revenue loss | % | II Compensation payments | III FCD contribution | % | |

| Ivory Coast | 605,7 | 26,6 | 403,9 | 791,4 | 61,5 |

| Senegal | 190,4 | 8,3 | 126,9 | 426,5 | 33,1 |

| Upper Volta | 631,9 | 27,6 | 421,2 | 45,3 | 3,5 |

| Mali | 183,7 | 8,1 | 122,4 | 17,0 | 1,3 |

| Niger | 220,1 | 9,7 | 146,7 | 6,9 | 0,5 |

| Mauritania | 448,8 | 19,7 | 299,3 | 0,5 | 0,1 |

| 2280,6 | 100,0 | 1520,4 | 1287,6 | 100,0 |

Source: Data from the Secretariat.

that the Ivory Coast and Senegal practically fund the FCD by themselves is no surprise. The discrepancy in the figures for Upper Volta provide the best illustration of a case of close integration into the Community's market for industrial products in conjunction with limited production of export-oriented industrial goods.

The FCD is considered a "revolutionary" element because it achieves fiscal compensation by “crediting” losses in customs revenues, and economic compensation by financing projects in the poor member states almost exclusively at the expense of the rich countries.

Differences in development levels

The above formula for redistribution will at first apply for five years only because it is assumed that the industrial imbalance will at least be reduced, if not eliminated altogether, at the end of that time.

In reality, this will not be the case, and the existence of a mechanism for redistribution will still be essential to the continued existence of the CEAO even after the initial period of five years. There are several reasons for this. The amount allocated for FCD-financed projects is relatively low and will not grow rapidly in the future because it is dependent upon the development of trade within the Community. In 1976, only 649 million CFA francs (= 28,5 percent)* of the available 2 280 million CFA francs (compare Table 2) was earmarked for development projects. Of all these projects, only one was of interest to the Community as a whole, while the others were exclusively of national or often of local importance only. Only a minority of the projects concerned the industrial sector or related areas. The compensation payments (1500 million CFA francs in 1976 according to Table 2)** are given to the various countries to do with as they choose, and their effect with respect to decreasing the existing economic imbalance can hardly be measured. On the whole, the effect is probably low because the planning and execution of national projects is still in the initial stages in all the countriesIn addition, the advantageous location of industry in the coastal countries, especially in the larger metropolitan areas of Abidjan and Dakar where the effects of urban agglomerations (still) tend to reduce costs, cannot be easily compensated for, no matter how attractive investment conditions and customs advantages are in the othercountries. A reorientation of the flow of investment capital cannot be anticipated until Abidjan and Dakar become "too expensive", and industrial as well as commercial considerations provide definite incentives to relocate. However, this only represents a long-term possibility.

Focal points of further CEAO development

Following the initial phase of the CEAO, it has up to now hardly been possible to make any

- * The distribution was as follows: 206 million CFA francs for Upper Volta and Mali, 160,7 million CFA francs for Niger, and 76,1 million CFA francs for Mauritania.

- ** The remainder is for expenditures incurred by the General Secretariat for a survey of 5 percent and a special investigation of waste and corruption.

statements with respect to the success of the organization's other activities, including efforts to co-ordinate development plans, etc., because they are only now being dealt with in studies, seminars and recommendations in public. The various authorities for industrial development, agricultural development, the fishing industry, transport and communications, as well as the Office Communautaire du Bétail et de la Viande, (the Community Bureau for the Cattle and Meat Industries) the only body to have implemented concrete measures already, are all active at the present time.

At the beginning of this article, it was stated that the initial phase of establishing the CEAO is now considered to have come to an end. On the basis of the course of events during the CEAO summit conference in Abidjan in mid-1977 it would seem certain that the emphasis of Community activity in the second phase will shift to the harmonization of customs and tax policies, trade laws and development planning. The core of the Community, the FCD development fund, will have to be considerably expanded during this period. As of now, it is impossible to foresee how long this second phase will last. However, the Secretariat is confident that it will at least be possible to harmonize customs, tax and trade policies within a relatively short period of time because all CEAO countries have at least similar legal systems as a result of their common colonial past. However, adjusting development plans could prove more difficult because all the CEAO countries are still giving their own national problems priority.

Economic Community of West-African States

The pan-African circles which considered the CEAO to be ”a child born without hands and legs” (Sunday News, Dar es Salaam, 1973), especially because of Nigeria's non-participation, greeted the establishment of the ECOWAS with great expectations in 1975-1976. In addition to the creation of a customs union, this organisationof 16 member states attempted to harmonize industrial development in three stages, to develop a common agricultural policy and a common traffic policy, and to create a multilateral balance-of-payments system. The Fonds Communautaire de Coopération, Compensation et Développement constitutes an important Community tool. It is funded by contributions from the 16 member states in accordance with a formula which takes into account the GNP and the per capita income to the same extent. This most recent of West African attempts at integration will only be dealt with briefly below.

There are essentially two reasons for this: Certain parts of this Community have only been in existence since 1977, making even a preliminary evaluation of its success impossible; and one cannot completely reject the possibility that the ECOWAS simply represents another still-born union on the African continent which has already experienced so many abortive attempts at integration (Le Monde Diplomatique, 1975; Langhammer, R J , 1976; Ezenwe, Uke, 1976; & Afrique Contemporaine, no. 88, p.13—21). The simple fact is that merely adding countries together does not yield any sort of community.

Heterogeneity of member states

The membership of Nigeria, an OPEC country, would seem to represent a crucial problem for the success of the ECOWAS. Nigeria's population is greater than that of all of the other 15 partner countries together, and its GNP amounts to almost 60 per cent of that of all ECOWAS countries combined. The history of European unity shows all too clearly what problems can result from domination by one member country. These problems are even more acute in West Africa because Nigeria's predominance in West Africa is much heavier than that of the Federal Republic of Germany in Western Europe. In this context, it would be appropriate to recall that some of the founders of the CEAO established this organisation in order to create a counterweight to Nigeria‘s superiority in the region. Other obstacles that are just as important and which are for the most part unknown within the relatively homogeneous CEAO group stand in the way of the successful implementation of the ECOWAS. To mention only two examples, it will be difficult to adjust tax incentives for private foreign investment in the People's Republics of Benin and Guinea, which have aligned themselves with scientific socialism, with those in Nigeria and the Ivory Coast, which are oriented toward capitalism, and one must question whether it will be possible to harmonize their development plans. Even today, it happens often enough that there are no direct telephone links between neighbouring

English and French-speaking countries, not to mention road and railway connections (von Gniellinski, S., 1977.) As a result, trade between English and French-speaking countries often does not amount to as much as that within the CEAO.

What will the liberalization of trade that was emphasized in the ECOWAS agreement achieve?

Even where relatively favourable preconditions exist for liberalising trade, that is, where trade between countries is already well developed, the implementation of such a policy is generally blocked by restrictions on the convertibility of currency and the flow of capital. Finally, the fact that the arrangements for making payments to and receiving funds from the compensation fund of the ECOWAS have not been formulated nearly as concretely as those of the corresponding CEAO fund (FCD) would seem to be significant.

Compatibility of the ECOWAS and CEAO charters

If the ECOWAS should nevertheless be successful in the future, the question as to how compatible the charters of these two communities are, is bound also to come up in actual practice with respect to policy. In other words, would the charters of these two communities allow the CEAO to consider itself as the core of the largerECOWAS, as is the case with the Benelux countries within the EC? The Abidjan agreement which established the CEAO, contains specific provisions for gradually eliminating domestic customs duties that have been levied on trade in various groups of products within the CEAO area (von der Ropp, K, op.cit., p 471—473). The Lagos agreement, by virtue of which the ECOWAS was founded, contains practically no provisions in this respect. One way to remedy this situation would be to have the ECOWAS take over the CEAO arrangement that has been so thoroughly thought out. The same would apply for the abovementioned mechanisms designed to achieve a financial balance between countries of the two communities. On the other hand, it is quite conceivable that the CEAO countries will for the most part adjust their development, industrialization and agricultural policies in accordance with the Abidjan agreement but that this will not be the case within the ECOWAS. However, there is at least one obstacle which seems insurmountable, and that is Article 59, paragraph 2, of the Lagos agreement that states that the rights and obligations of the signatory countries from previous agreements (including the Abidjan agreement) will not be affected by the agreement to establish the ECOWAS. In accordance with Article 59, paragraph 3, of the Lagos agreement, the parties do, however, bind themselves to a gradual reduction of their respective rights and obligations in conflict with the ECOWAS agreement. Together with Article 20 of the Lagos agreement (preferential treatment clause), this means that the CEAO countries must extend to all countries belonging to the ECOWAS, all CEAO preferences, in other words, that the CEAO customs union must be gradually dissolved. For the present at least, there is nothing to indicate that the "Six de l’Afrique” are prepared to do so. In conclusion, it is possible to state that the CEAO definitely gives ground for hoping that African countries are on their way to a relatively stable form of close co-operation, whereas the same cannot be said of the ECOWAS.

References

- Baumhoger, G. 1976. Kontinuität oder Neuasrichtung? Eine Bestandsaufnahme der Ostafrikanischen Gemeinschaft, in Leistner, G.M.E. & Breitengoss, J P in Afrika. Institut für Afrika-Kunde, Hamburg, p. 1—93. See also von der Ropp, K. Freiherr, 1971. Chancen für eine Föderation in Ostafrika? Aussenpolitik, vol. XXII, no 2, p 105-109.

- Von der Ropp, K, Freiherr, 1971. Ansätze zu regionaler Integration in Schwarzafrika. Europa-Archiv, vol XXVI, no. 12, p 429—436.

- According to Le Moniteur Africain (Dakar) 1973, April 19, p1.

- According to President Felix Houphouet-Boigny of Ivory Coast in Jeune Afrique (Paris) 1977, June 24, p 23.

- Probably the best survey of the actual network of French-African relations is to be found in Scherk, N. 1968. Dekolonisation und Souveränität. Vienna and Stuttgart.

See also von der Ropp, Freiherr. 1974. Die Franko-afrikanischen Beziehungen. Aussenpolitik, vol XXV, no, 4, p 461—476. - Langhammer, R J 1973. Die Westafrikanischer Wirtschaftgemeinschaft — Ein neuer Weg zur regionalen Integration West-Afrikas? Internationales Afrika-Forum, vol IX no 7 and 8, p 408—420.

See also von der Ropp, K, Freiherr. 1973. Die Westafrikanische Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft. Aussenpolitik, vol XXIV no 4, p 467-475.

Cf. Mytelka, Lynn K. 1974. A Genealogy of Francophone West and Equatorial African Regional Organisation. TheJournal of Modern African Studies, vol XII, no 2,

- p 297—320 (with comprehensive bibliography).

- Figures for 1970 according to Le Soleil (Dakar) 1973, April 18, p 4.

- See here CEAO/Politiser l'organisation pour faire revivre la communauté. Jeune Afrique, (Paris) 1977, May 13, p 33.

- See here von der Ropp, K Freiherr. Die Westafrikanische Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft. Op.cit., p 472—473.

- According to the Sunday News (Dar es Salaam) 1973. June 3, p 3.

- The ECOWAS or CEDEAO agreement was to some extent regarded with scepticism by Penouil, Marc. Le Traité de Lagos efface le clivage entre pays francophones et anglophones. Le Monde Diplomatique, (Paris) 1975,October 24.

Langhammer, R J 1976. Die Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft westafrikanischer Staaten (ECOWAS). Ein neuer Integrationsversuch. Europa-Archiv, vol XXXI, no 5, p 163—168.

See also Ezenwe, Uke. 1976. The way ahead for ECOWAS. West Africa, (London) 1976, September 20, p 1355—1357. Also 1976 September 27, p 1403-1404.

The ECOWAS or CEDEAO agreement is reprinted in Afrique Contemporaine (Paris), no 88, p 13—21. - See here the recent contribution by von Gnielinski, Stefan. 1977. Die entscheidene Rolle der Verkehrserschliessung für die regionale Entwicklung Westafrikas. Internationales Afrika-Forum vol XIII no 3, p 259—274.

- Von der Ropp, K Freiherr. Die westafrikansche Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft. Op.cit., p 471-473.